With Bitcoin surging in price – and into investors’ consciousnesses – Carbon Growth Partners CEO Rich Gilmore explores crypto’s parallels to carbon markets, and finds that while the similarities are superficial, the differences are profound^.

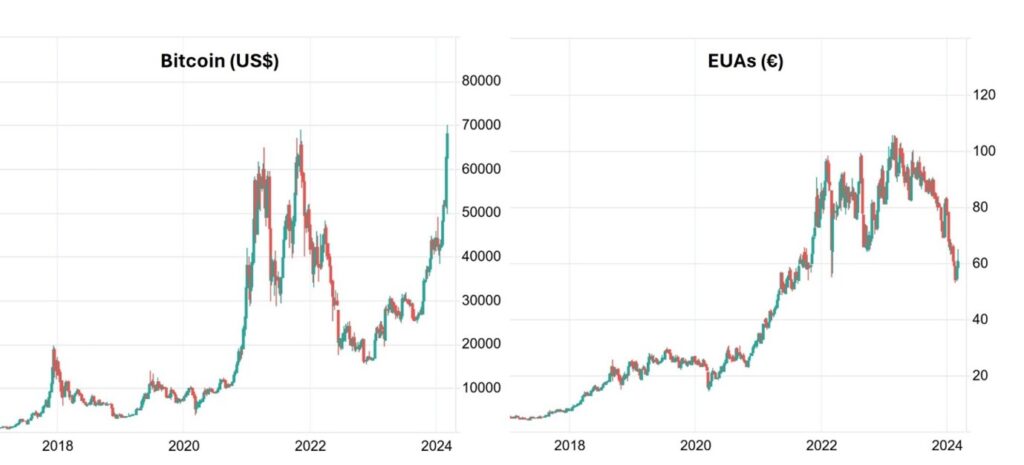

It won’t have escaped your attention – or anyone else’s – that Bitcoin has surged back to all-time price highs, topping US$69,000 in March, and bringing with it renewed interest from FOMO-driven investors. The resurgence is reminiscent of the strong rally in carbon prices either side of the COP26 in late 2021 and 2022 and the subsequent rally that took prices to record levels above US$100 a tonne in 2023.

There are indeed similarities: both are digital assets with constrained supply; Bitcoin is the currency of digital finance, while carbon credits and allowances are the currency of decarbonisation; and prices of both have risen by many mutiples over the past decade.

But is that where the similarities start and end? Let’s take a look at three cases for, and three against…

Why carbon is like Bitcoin.

- Forced scarcity

Perhaps the most important design feature shared by carbon and crypto markets is controlled supply. In Bitcoin, this supply is governed by the network protocol, which caps the number of Bitcoin that can ever be created, and the speed at which this can be done.

In compliance cap-and-trade carbon markets, supply is controlled by an emissions allowance cap, in which the cap reduces over time. In the VCM, supply is controlled by ever-tightening eligibility rules and revisions to methodologies that raise the bar of additionality and make carbon credits harder and more expensive to create.

In the VCM, major protocol updates can serve the same function as the ‘halving‘ in Bitcoin and can have just as dramatic an effect. Take for example, the update by Verra to the Verified Carbon Standard in 2020/21. This update – Version 4.3 – withdrew the carbon credit eligibility of almost every new renewable energy project in all but the world’s very poorest countries, and severely curtailed others. This had the effect of cutting off the source of around 45% of historical supply. The effect of this ‘VCM halving’ has not yet been fully felt, because existing VCM projects were grandfathered in for seven years to protect investment confidence; as those projects start to roll out of the system in coming years, unwary buyers will start to fell the squeeze.

And while carbon markets don’t have the same ‘hard’ supply caps as Bitcoin, supply is much more inelastic: a higher carbon price won’t make a tree grow any faster, organic waste rot any slower, or soil microbes work any harder.

- “Transparent opacity”

While carbon market ETFs like Krane Shares’ KRBN have existed for years – and were recently joined by Bitcoin ETFs – for many investors the mechanics of how these markets work can seem opaque and confusing. There’s plenty of irony in that, given transparency and open sourcing are such key design features of both commodities.

- One-way price traffic, with some detours en route

The prices of carbon and Bitcoin have both increased by many multiples over the past decade. After a staggering run up during and post-COVID, in 2022-23 Bitcoin crashed to less than half its peak value, before recovering to post all-time highs in March 2024.

The EU Emissions Trading System – the best carbon market comparator given its scale, liquidity and longevity – has seen allowance prices rise from below US$5 a tonne in 2013-14 to more than $100 a tonne in 2023. While early 2024 has seen prices retrace from those highs, the EU carbon market also saw selloffs during the global financial crisis, during COVID, and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Each time it has recovered to post new highs.

The outlook for carbon pricing remains bullish in the estimations of most, with Bloomberg NEF projecting prices could reach as high as $238 a tonne by 2050.

Price charts for Bitcoin and EU Allowances. Source:

And why it isn’t.

- Authenticity of demand, and one-time use.

Unlike Bitcoin, carbon credits have sources of intrinsic demand for use cases that are observable, growing, and in some cases, mandatory.

The whole point of Bitcoin, as its creator “Satoshi Nakamoto” stated in the 2008 white paper outlining the concept, was that: “A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution”

The problem is, unless you count the infamous $600 million dollar pizza delivery, almost no-one uses Bitcoin for its intended purpose: to actually buy things [Ref].

In carbon markets, the opposite of true. In the three months since COP28, 19 million more carbon credits were used for emissions offsets across the main registries, than were created – meaning total supply fell by that number – and over the past three years, more than half of all carbon credits created have been ‘destroyed’ – that is, they have been used as an offset and retired.

The demand for carbon credits is intrinsic: they offer companies and countries pathways to meet their necessary net emissions reduction targets that would not otherwise be open to them. The convergence of compliance markets and ‘verified’ or ‘voluntary’ markets means more of this demand is being driven by the requirements of law, alongside the requirements of stakeholders.

And there’s another big difference: one-time use. In the event someone does make a purchase of goods using Bitcoin, the merchant is able to use that Bitcoin to make another purchase and so on, ad infinitum.

Not so in carbon markets: once a carbon credit has been used for its intended purpose – its retirement as an emissions offset – it ceases to exist and has to be replaced, usually with one that was more time consuming, difficult and costly to produce.

- Climate impact: a vicious, or virtuous cycle?

Every time a Bitcoin is created, the climate has been harmed. Every time a carbon credit is created, by definition the climate has been helped.

This is a big one.

The emissions from creating or ‘mining’ Bitcoin are immense: estimated to be more than 60 million tonnes a year.

Those negative emissions are driven by the colossal amount of energy needed to mine Bitcoin. The University of Cambridge’s most recent Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI) found that Bitcoin mining is devouring 100 terrawatt (TWh) hours of energy every year, around half of which comes from fossil fuels. Even when partially powered by cleaner energy sources – such as co-located geothermal and hydro – the opportunity cost is immense: an electron can’t be in two places at once (or can it?) and those electrons could be better spent lighting and cooling homes and hospitals and lifting people out poverty. To put this amount of energy into context, 100 TWh would double the amount of electricity available to six million people in Africa.

According to the United Nations, the negative impacts of Bitcoin affect more than just the climate: “Bitcoin’s water footprint is similar to the amount of water required to fill over 660,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools, enough to meet the current domestic water needs of more than 300 million people in rural sub-Saharan Africa. The land footprint of worldwide Bitcoin mining activities is more than 1.4 times the area of Los Angeles”.

And the pricing cycle is a vicious one: As Bitcoin prices rise, more miners boot up, seeking to cash in and munching through ever more energy, water and land.

The contrast with carbon credits is diametrical: every carbon credit created represents one tonne of CO2 avoided or removed from the atmosphere. This cycle, however, is a virtuous one: with rising carbon prices comes more conservation and protection of forests and wetlands, more safe cooking for vulnerable families, more clean afforable energy, more waste diverted from landfill, and a stronger incentive for polluters to avoid their emissions in the first place.

- Existential importance, and no substitution

In my personal pension plan, I hold just three assets: land, water, and carbon credits*. Land is the ultimate real asset, while water and carbon share three attributes that are true only of them: water and carbon are only two commodites that:

- are tradeable in large and liquid markets (global carbon markets turn over more $800 billion a year); and

- are essential for all life on Earth (literally); and

- have no substitute (Don’t like one kind of crypto? There’s always another kind. Or cash. Or bonds. Or gold. But how are you going to substitute the carbon and water in your body, in plants, animals and soils?)

Bitcoin may share the first of these three attributes, but in the long game the other two will matter much, much more.

—

^Information in this article is general in nature and does not constitute financial advice nor an offer of securities. You should do your own research before making investment decisions considering your own circumstances.

*Through the funds we manage, of course.